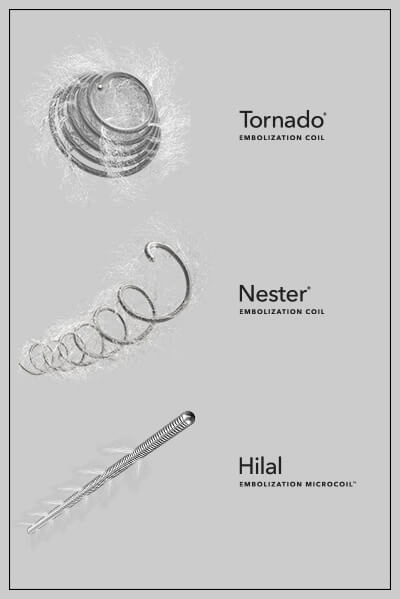

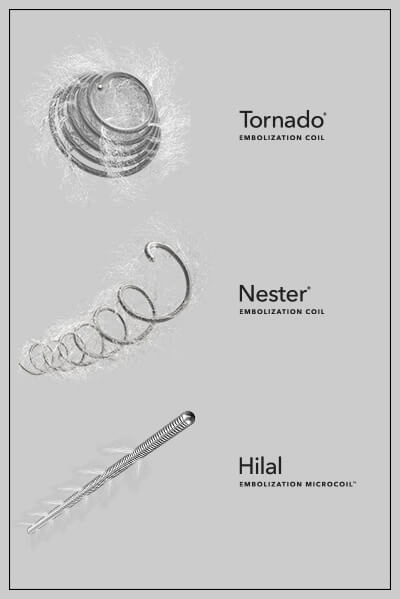

According to “Nylon fibered versus non-fibered embolization coils: comparison in a swine model,” an animal study authored by interventional radiologist Dr. Scott Trerotola, from the University of Pennsylvania, embolization coils with nylon fibers allow significantly fewer embolization coils to achieve acute occlusion of arteries compared to bare metal coils.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether nylon fibers improve the performance of platinum embolization coils in porcine arteries. The study tested the efficacy of platinum embolization coils, with and without nylon fibers, in the hindlimbs of six juvenile pigs. A total of 24 coils were used—12 with fibers and 12 without fibers. Specifically, the study looked at the number of coils needed to achieve vessel occlusion and the durability of occlusion at 1 and 3 months.

The study found that fewer fibered coils were needed to achieve acute occlusion compared to bare metal coils. A mean of 3.2 bare metal coils was required to achieve occlusion, while a mean of only 1.3 fibered coils was necessary to occlude the targeted vessels. Both fibered and non-fibered coils showed similar rates of recanalization at follow-up.

The study, which was randomized and blinded and utilized a single operator to eliminate experimental bias, is among the first to provide strong evidence supporting what clinicians have long observed: that fibers enhance thrombogenicity. Although some early studies suggested that fibers benefit occlusion, the coil and fiber material used in those studies differs from material in devices used today. The present study compares modern platinum coils both with fibers and without and was designed to limit variables to the greatest extent possible.

The study does provide strong evidence that the incorporation of nylon fibers in metallic embolization coils has been shown to significantly reduce the number of coils required to occlude peripheral arteries. Based on the results of the study, in the setting where acute occlusion is important, it would appear that fibers have an advantage over non-fibered coils.

To read the details of this statistically significant, peer-reviewed in-vivo study published in JVIR, go here.

Dr. Trerotola is a paid consultant of Cook Medical.

IR-D48664-EN

Blood may be the essence of life, but there are times when a physician needs to stop or redirect blood flow to treat a patient or even save his or her life. Using minimally invasive interventional techniques–an alternative to open surgery–embolic agents can be delivered through a microcatheter and implanted in tiny blood vessels to cut off blood supply to a particular area of the body. “Coils and particles stop blood flow by creating an occlusion,” said Clint Merkel, global program manager responsible for the Cantata Microcatheter line.

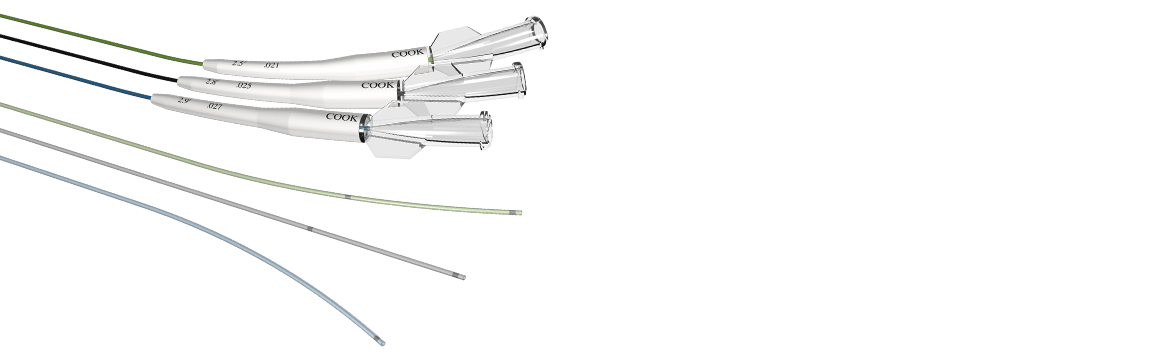

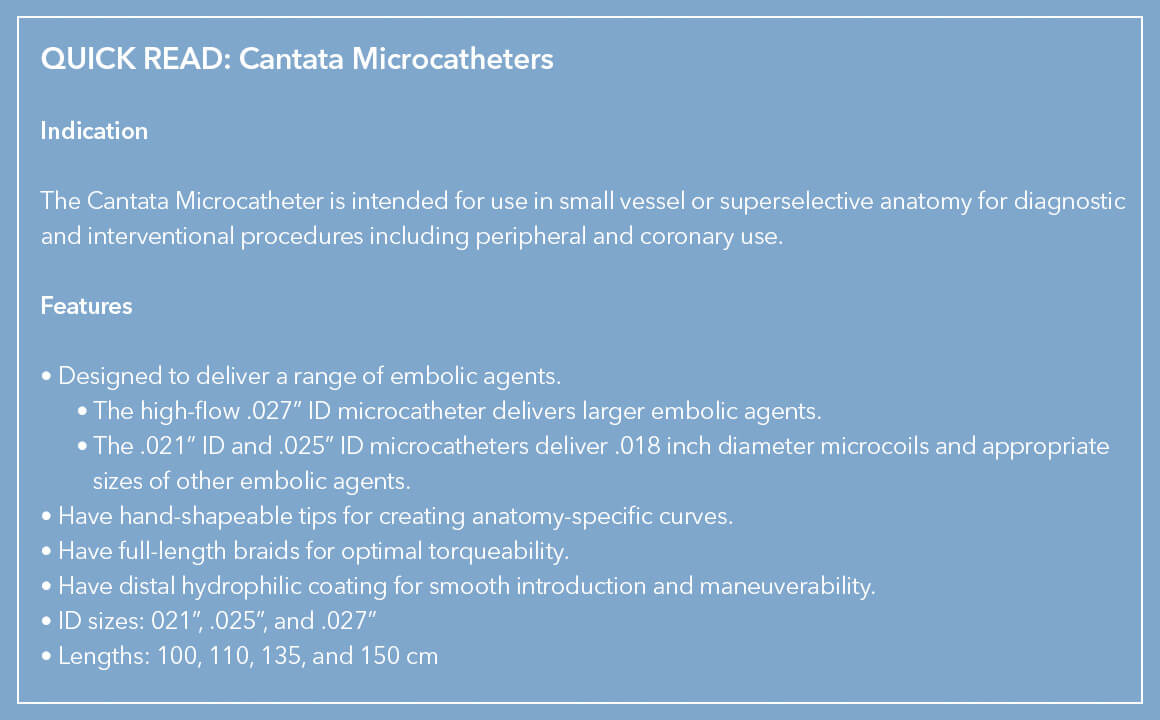

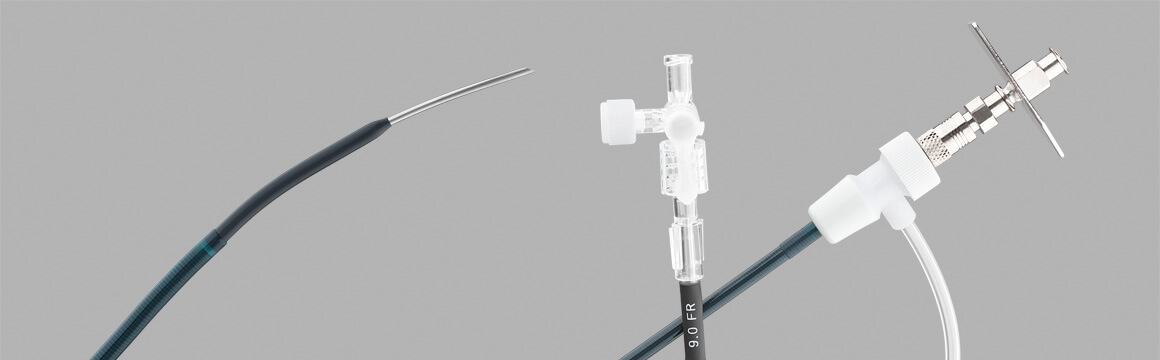

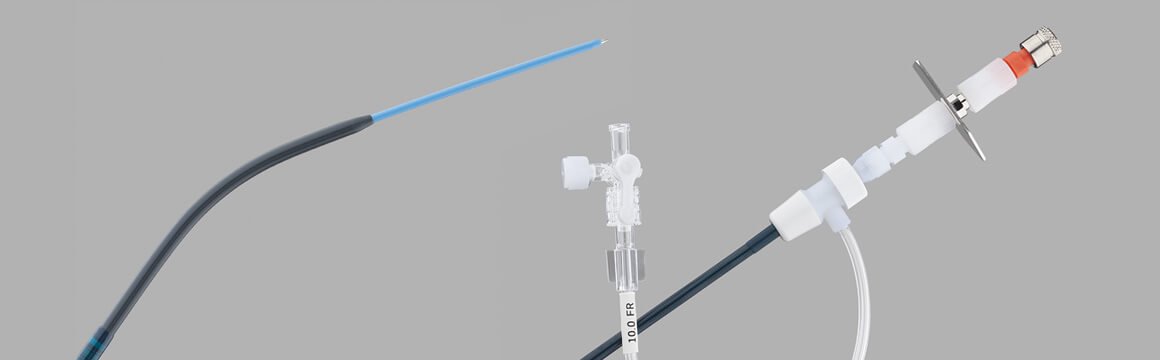

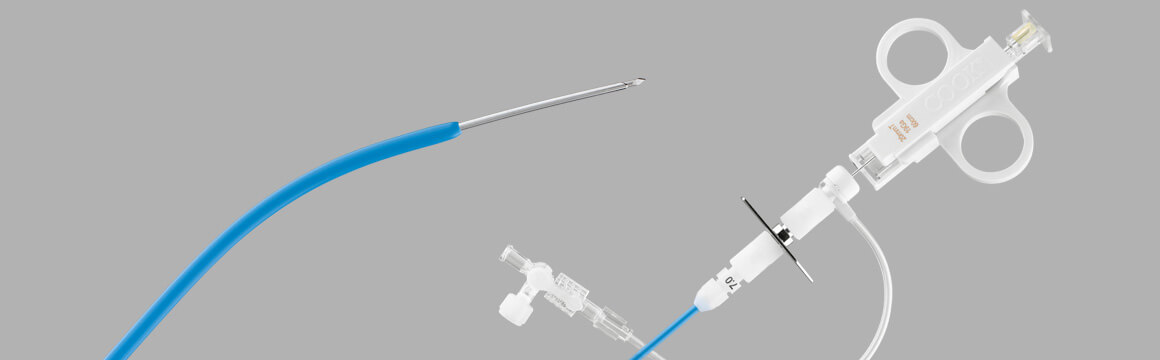

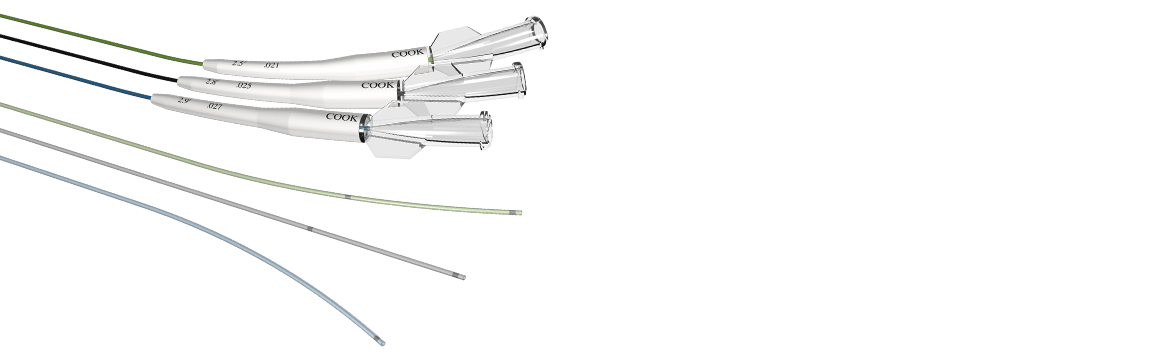

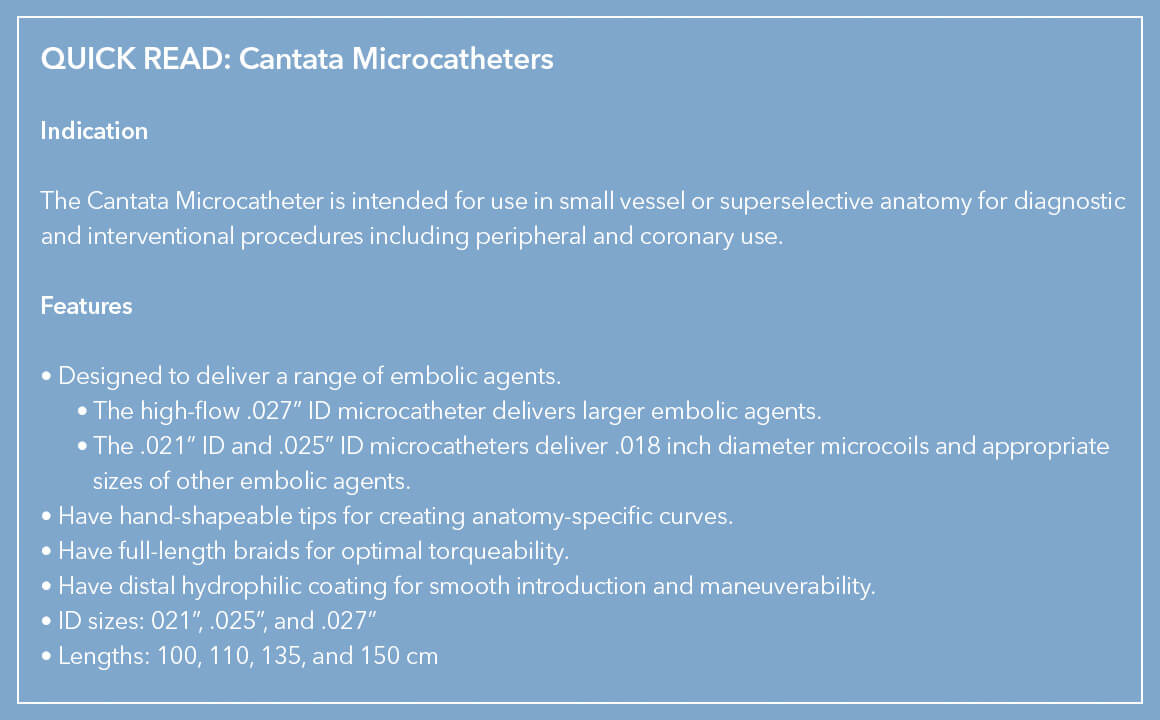

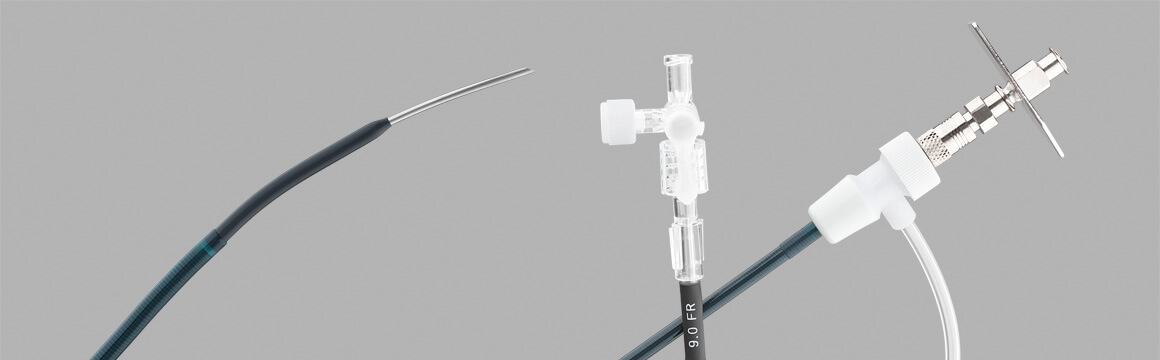

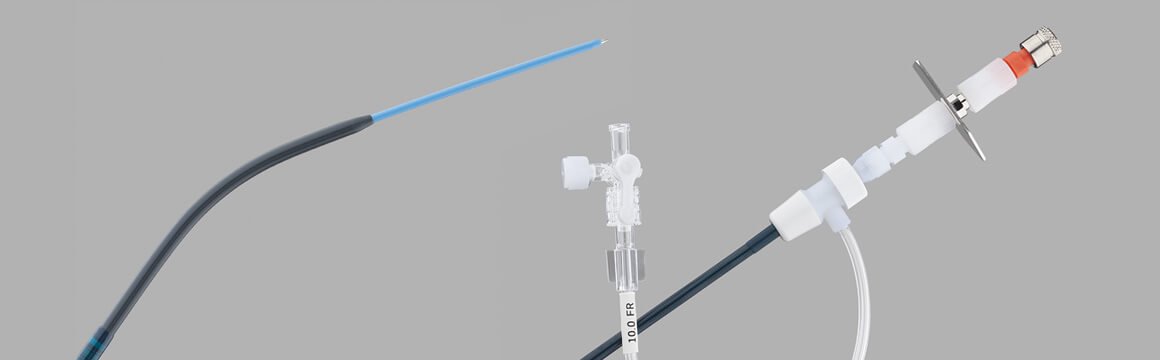

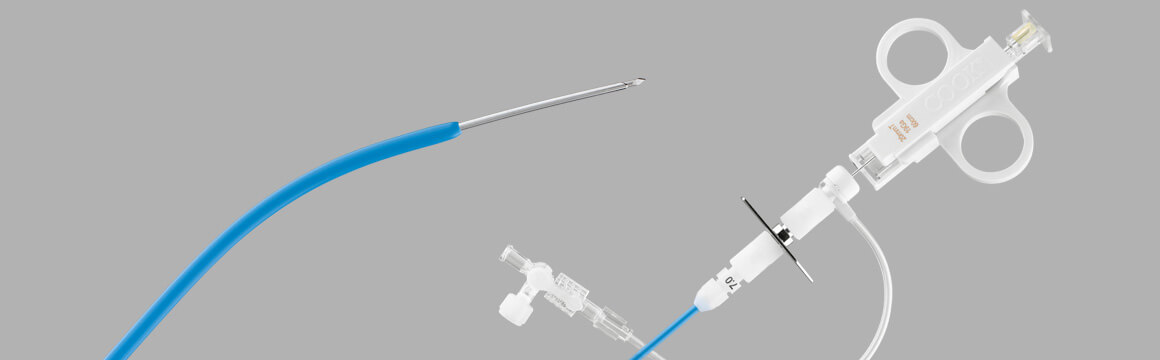

Between them, Cook’s family of three Cantata Microcatheters are designed to deliver particles such as non-spherical PVA Foam Embolization Particles and microsphere, embolization coils, and other embolic agents, including glue or alcohol fluid, to very small vessels in the peripheral vasculature. The high-flow .027” inner diameter (ID) Cantata Microcatheter delivers relatively larger embolic agents to target anatomy while the .021” ID and .025” ID Cantata Microcatheters deliver .018” diameter microcoils and appropriate sizes of other embolic agents.

Between them, Cook’s family of three Cantata Microcatheters are designed to deliver particles such as non-spherical PVA Foam Embolization Particles and microsphere, embolization coils, and other embolic agents, including glue or alcohol fluid, to very small vessels in the peripheral vasculature. The high-flow .027” inner diameter (ID) Cantata Microcatheter delivers relatively larger embolic agents to target anatomy while the .021” ID and .025” ID Cantata Microcatheters deliver .018” diameter microcoils and appropriate sizes of other embolic agents.

Particles can be used where coils are too large, or where there are networks of small blood vessels feeding a tumor, fibroid, or arteriovenous malformations. “Because of their small size, particles can reach deeper into smaller arteries and wedge themselves there to stop the blood supply,” Clint explained. “Depending on the particle size needed, there is a Cantata Microcatheter to help deliver the agent.”

Each of the Cantata Microcatheters has a maximum particle size limit: 500 μm for the 2.5 Fr superselective Cantata, 700 μm for the 2.8 Fr superselective Cantata, and 1,000 μm for the 2.9 Fr high-flow Cantata.

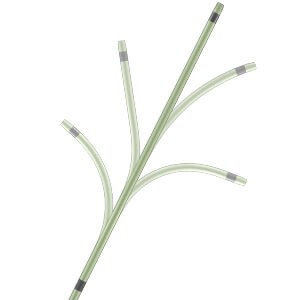

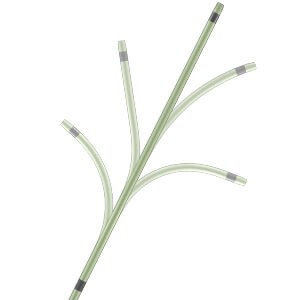

A unique feature of all Cantata Microcatheters is that their tips can be shaped by hand. This gives physicians several options for optimal access to difficult anatomy. “Cantata is designed to navigate through tortuous anatomy,” said Albert de Troije, EMEA area program manager for Cook’s embolization devices. “You can shape the tip by hand to create curves that complement specific anatomy. It doesn’t require heat or steam. Cook has the only device on the market like this because of the proprietary braid that runs the length of the microcatheter.”

A unique feature of all Cantata Microcatheters is that their tips can be shaped by hand. This gives physicians several options for optimal access to difficult anatomy. “Cantata is designed to navigate through tortuous anatomy,” said Albert de Troije, EMEA area program manager for Cook’s embolization devices. “You can shape the tip by hand to create curves that complement specific anatomy. It doesn’t require heat or steam. Cook has the only device on the market like this because of the proprietary braid that runs the length of the microcatheter.”

The hand-shapable feature of Cantata Microcatheters enable physicians to make anatomy-specific curves.

Besides the unique hand-shapability of the braid tip, the microcatheter design also provides control, torquability, and kink resistance. To enable optimal trackability, Cantata’s full-length stainless-steel braid has five transition zones that provide a distinct yet seamless transition from hub to tip. The braid also has a distal hydrophilic coating to ensure smooth introduction and maneuverability through arteries and veins.

To view the flow rate chart of different infusion mediums in the three Cantata Microcatheters, as well as ordering information, go here.

IR-D67689-EN

By using what is at hand, adapting existing tools to new uses, and conceiving of entirely new solutions, innovative Cook product-development staff and brilliant physicians and technicians have collaborated to develop, evaluate, and perfect interventional devices for over 50 years.

By using what is at hand, adapting existing tools to new uses, and conceiving of entirely new solutions, innovative Cook product-development staff and brilliant physicians and technicians have collaborated to develop, evaluate, and perfect interventional devices for over 50 years.

This solution-seeking synergy is seen in the evolution of Cook’s liver access and biopsy sets, referred to as the RING, the RUPS, and the LABS sets. These sets are still being used in interventional procedures 20 years after they first came to market. To find out more about the role they played in the advancement of the field of interventional radiology, we talked with some of the key innovators, both inside and outside of Cook, who collaborated to develop these sets: Dr. Ernest Ring, now retired from UCSF; Barry Uchida, X-ray technician and researcher at OHSU’s Dotter Institute; Joe Roberts, Cook VP of corporate development; and Ray Leonard, Cook global corporate development manager.

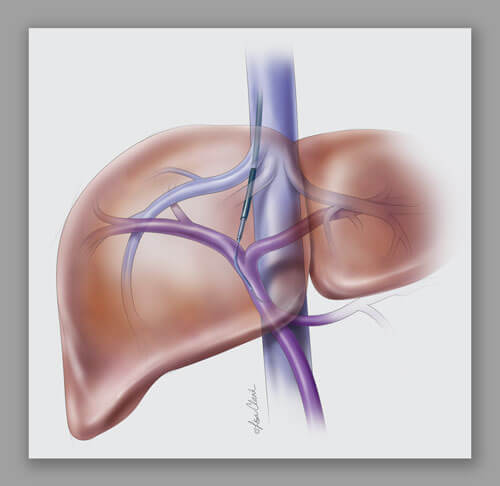

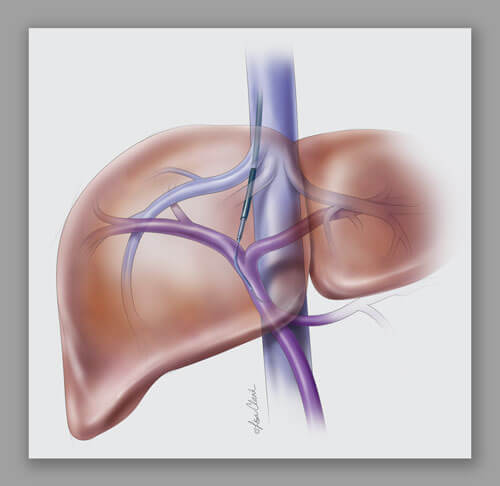

Both the Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING) and the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS) are often used during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. The sets’ components are used to access the liver using a transjugular approach and then create a pathway through the liver to connect the portal and hepatic systems, laying the groundwork for the placement of a stent.* Similarly, the Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS) uses a transjugular approach to take a biopsy of the liver.

Both the Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING) and the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS) are often used during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. The sets’ components are used to access the liver using a transjugular approach and then create a pathway through the liver to connect the portal and hepatic systems, laying the groundwork for the placement of a stent.* Similarly, the Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS) uses a transjugular approach to take a biopsy of the liver.

Dr. Ernie Ring: “Control was critical”

Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING), launched in 1991

Dr. Ring worked with Cook managers and engineers, particularly Joe Roberts, to find new ways to use an image-guided needle for liver biopsy and to use drainage catheters for percutaneous drainage of the biliary tree. Dr. Ring and other clinicians made use of the components from the Colapinto Transjugular Cholangiography and Biopsy Set** for accessing the liver. We asked Dr. Ring how he conceived of the idea for the RING set.

“I had been doing the same kind of procedure, using a long needle and going in from the side using a transhepatic approach. It occurred to me that I could make the procedure more efficient by going in from the top using a transjugular approach. I used what I had on the shelf, which was a Colapinto needle, invented by the late Dr. Ronald F. Colapinto of Toronto, and an Amplatz wire. The Colapinto was the right length, and the curve at its tip allowed it to be turned anteriorly. In the early days, if I needed anything, I’d just call Cook and they would build it for me.”

“Clinically, the big advantage of the RING is that it gives you the authority to redirect the needle,” continues Ring. “Once you get in, then it becomes a stiffening rod over which the sheath can advance. Some diseased livers are very hard but the RING set makes advancing a balloon* possible.”

“Scaling up from a 5 Fr system to a 9 or 10 Fr sheath was an easy adjustment that enabled a balloon* or stent* to pass through. Also, the Colapinto needle worked well because it is a hollow biopsy needle. The hollow needle created a passage through the liver and allowed you to check blood flow.”

Barry Uchida and Josef Rösch: innovating for physician preference

Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS), launched in 1992

Barry Uchida, a former X-ray technician who later became a researcher at the Dotter Institute, was deeply involved in the development of the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set. “We started developing the RUPS in 1988, when pioneers Charles Dotter and Josef Rösch were using the Colapinto needle to access the bile ducts for cholangiography. Dr. Rösch deserves credit for giving me the opportunity to develop ideas and for guiding me during the process. He was not only my boss, he was my partner and a true pioneer.” (Read our tribute to the late Dr. Rösch.)

Explains Uchida, “The RUPS overcame a clinical challenge for us because the set’s 14 gage cannula is more flexible compared to the Ring set. The RUPS also provides access without the frequent exchanges of multiple wire guides and catheters.”

Dr. Fred Keller, who was chief of the Dotter Institute then, began using the RUPS around 1993. Uchida says that Dr. Keller liked the RUPS because the puncture needle was smaller than the RING set needle. He also liked the fact that, as with the RING set, the catheters and dilators are all together in one set, and it is easier to place commonly used stents* through the 10 Fr Flexor® sheath.

Ray Leonard’s resourcefulness

Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS), launched in 1994

Since Cook already had an inventory of soft tissue biopsy needles, and now had devices to access the liver, it only required one more step to provide a solution for gathering liver biopsies. Ray Leonard recalls, “I had the idea to pull the RUPS-100 set from stock and run the 18 gage Quick-Core® needles inside of them. Inside of the cannula the needle bound and grated during advancement, but the spring still fired. After further refining the idea, I sent the idea off to Hans Timmerman at the Dotter Institute to see if the concept worked. It did.”

Ray and his colleagues then worked with staff at the Dotter Institute and other institutions to evaluate the prototype LABS product. “Dr. Ernie Ring was one of the approximately seven clinicians who received clinical prototypes from Cook. Each evaluator gave us valuable input, including feedback from their pathologists. I remember sending each evaluator a thank you letter, attached to a data sheet showing the finished LABS product, to recognize them for their input,” adds Ray. A short time later, the LABS was launched as a transjugular liver biopsy solution.

RING versus RUPS: which would you prefer?

While the RUPS and RING accomplish the same goal of access to the liver, physicians today choose the set that best fits their technique. For physicians wanting to learn how to use these Cook devices, training courses involving didactic presentations, table top models, and hands-on animal labs are offered through Cook’s Vista® Education and Training Program at vista.cookmedical.com.

To learn more about each set, click on the links below to view our RING, RUPS, and LABS instructions for use, animations, and illustrated guides:

RING product page

RUPS product page

LABS product page

* Balloons and stents are not included in the RUPS or RING liver access sets.

** Now discontinued.

IR-D45651-EN

We sat down with Dr. David Beckett, an interventional radiologist at The Whiteley Clinic in London, England, to talk about pelvic congestion syndrome. Dr. Beckett explained the reasons why this painful disease is underdiagnosed and the importance of collaboration among physicians and device companies to get these patients back to living.

We sat down with Dr. David Beckett, an interventional radiologist at The Whiteley Clinic in London, England, to talk about pelvic congestion syndrome. Dr. Beckett explained the reasons why this painful disease is underdiagnosed and the importance of collaboration among physicians and device companies to get these patients back to living.

At some point in their lives, approximately 39% of women suffer from chronic pelvic pain. A common but little known cause is pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS). PCS may affect 10% of women of childbearing age.

What is PCS?

In general, PCS is marked by varicose veins in the lower abdomen and pelvis. Because there’s little published data on PCS and no generally accepted or well-defined clinical criteria for its diagnosis, the condition has often been misunderstood and used as a diagnosis of exclusion.

“Perhaps, unlike cancer where a scan and biopsy can give a definitive diagnosis, PCS relies on a subjective set of symptoms acquired during a thorough history from the patient married with the results from a highly skilled transvaginal and transabdominal scan from trained professionals,” said Dr. David Beckett of The Whiteley Clinic in London. “The skills involved in this type of scan cannot be underestimated, and I’m lucky to work with some of the most highly skilled sonographers at the clinic.”

Adding to this challenge of consensus, pelvic congestion syndrome is not always a universally used name in literature. It’s sometimes referred to as chronic pelvic pain syndrome, female pelvic varicocele, pelvic venous incompetence, varicose disease of pelvic veins, pelvic varicosity, and pelvic venous congestion.

Symptoms and causes

While the symptoms of PCS are often varied and sometimes vague, patients typically present with a dull aching pain similar to what is felt with varicose veins in the extremities. Complaints may include a dragging sensation in the pelvis, a feeling of fullness in the legs, worsening stress incontinence, or symptoms associated with a urinary tract infection or irritable bowel syndrome. Pain may worsen prior to menses, with fatigue, extended sitting and standing, and following sexual intercourse.

Women suffering from PCS may report a general lack of energy, depression, abdominal or pelvic tenderness, vaginal discharge, dysmenorrhea, swollen vulva, lumbosacral neuropathy, and/or rectal discomfort.

Akin to varicose veins within the legs, there is a strong familial correlation. “Multiple pregnancies and estrogen overstimulation are associated with a higher frequency of cases,” Dr. Beckett explained.

In addition to weight gain and anatomic changes associated with pregnancy, ovarian vein flow can increase by 60 percent. Multiple pregnancies have a cumulative stress effect on the ovarian vein. The engorgement stretches the intima of the ovarian vein which could lead to venous valve incompetence. Blood pooling in the pelvic and ovarian veins may cause further engorgement, thrombosis, and an effect on nearby nerves, collectively contributing to pelvic pain.

Another potential cause of PCS is left renal vein entrapment associated with Nutcracker Phenomenon. The renal vein could be compressed between two abdominal arteries (anterior) or between the artery and the spine (posterior). According to Dr. Beckett, this represents a small proportion of cases, but an important group of patients.

A long road to diagnosis

Obtaining a diagnosis for PCS can prove to be a long and frustrating battle. Because patients suffer from such a wide variety of symptoms, they often end up visiting many physicians and specialists over the course of years, who either might not be aware of the disease or are unwilling to acknowledge its existence. A referral to an interventional radiologist is often made after all other potential causes are ruled out.

Patients presenting with pelvic pain may have underlying conditions such as endometriosis, fibroid disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, PCS, or any combination of these. “It is therefore important that gastro-intestinal, gynecological, vascular, pain specialists, and IRs collaborate in the management of PCS. Early and appropriate diagnosis will ease the burden on the health economy,” Dr. Beckett said.

When a patient presents with pelvic pain, most physicians rely on pelvic ultrasound and/or CT scan. While these modalities are effective for ruling out other pathologies, they have a relatively lower sensitivity for diagnosing PCS.

According to Dr. Beckett, a combination of transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasounds is needed to assess direction of blood flow and functionality of the vein. “MRIs only give an anatomical answer to whether the vein is large or small,” he said. “In fact, the ovarian vein diameter might be irrelevant. Quite frequently, small veins can have significant congestion and reflux. The transabdominal ultrasound checks for vein reflux and helps rule out compressions such as Nutcracker Syndrome.”

Transvaginal ultrasound further clarifies the nature and site of the reflux in the pelvis. “Studies have shown that the left ovarian vein alone is infrequently involved and the most common pattern includes the left ovarian vein and the internal iliac veins,” he added. “Currently there are few doctors experienced in treating internal iliac vein reflux.”

Advancements in treatment protocols

The current standard of PCS treatment for IRs is embolotherapy. “People across the world are doing different things,” Dr. Beckett explained. “The majority are using coils and some sclerosant foam while others use a Gelfoam with sclerotherapy combination.”

The technique of transcatheter embolotherapy for ovarian varices is straightforward. “Embolization of internal iliac veins is a more challenging treatment and reserved to those with experience in this field,” he said. “It is not uncommon to find cases taking several hours while, with increasing experience, these can be frequently completed within 30 minutes to one hour.”

According to Dr. Beckett, the learning curve may involve up to 50-100 cases. Veins identified on transvaginal scanning are then embolized leaving those that showed no evidence of reflux.

Collaboration is crucial

“Working toward a more effective collaboration between physicians and specialists as well as the medical device industry is key to getting PCS patients back to living pain free.”

In March, Cook Medical participated in the 2nd annual International Veins Conference in London. Vascular surgeons, interventional radiologists, podiatrists, tissue viability nurses, and community nurses from 33 countries attended the conference, which was organized by The Whiteley Clinic.

The program focused on the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome and the treatment of leg ulcers. Dr. Beckett performed a live-streamed PCS procedure from the clinic.

According to Dr. Beckett, the clinic’s goal is to bring greater awareness of PCS and encourage collaboration among primary care physicians and specialists to help ensure a speedier diagnosis. This will not only alleviate the patient’s pain and suffering, but will reduce the financial impact to the patient and the healthcare system.

“I have frequently seen patients who have waited more than 10 years for a diagnosis and treatment,” he said. “In this 10-year period, they have seen multiple specialists and underwent many diagnostic tests and invasive procedures with a huge burden on the health economy. The psychological impact of such delays weighs heavy on this group of patients. Equally, I have seen other causes for pelvic pain missed and so I look to the future of a collaborative approach for all patients in which PCS is not overlooked nor is it a diagnosis of exclusion.”

Read what societies have to say about PCS.

Pelvic congestion syndrome

Embolisation for pelvic congestion syndrome

Chronic pelvic pain (pelvic congestion syndrome)

IR-D45643-EN

Between them, Cook’s family of three Cantata Microcatheters are designed to deliver particles such as non-spherical PVA Foam Embolization Particles and microsphere, embolization coils, and other embolic agents, including glue or alcohol fluid, to very small vessels in the peripheral vasculature. The high-flow .027” inner diameter (ID) Cantata Microcatheter delivers relatively larger embolic agents to target anatomy while the .021” ID and .025” ID Cantata Microcatheters deliver .018” diameter microcoils and appropriate sizes of other embolic agents.

Between them, Cook’s family of three Cantata Microcatheters are designed to deliver particles such as non-spherical PVA Foam Embolization Particles and microsphere, embolization coils, and other embolic agents, including glue or alcohol fluid, to very small vessels in the peripheral vasculature. The high-flow .027” inner diameter (ID) Cantata Microcatheter delivers relatively larger embolic agents to target anatomy while the .021” ID and .025” ID Cantata Microcatheters deliver .018” diameter microcoils and appropriate sizes of other embolic agents. A unique feature of all Cantata Microcatheters is that their tips can be shaped by hand. This gives physicians several options for optimal access to difficult anatomy. “Cantata is designed to navigate through tortuous anatomy,” said Albert de Troije, EMEA area program manager for Cook’s embolization devices. “You can shape the tip by hand to create curves that complement specific anatomy. It doesn’t require heat or steam. Cook has the only device on the market like this because of the proprietary braid that runs the length of the microcatheter.”

A unique feature of all Cantata Microcatheters is that their tips can be shaped by hand. This gives physicians several options for optimal access to difficult anatomy. “Cantata is designed to navigate through tortuous anatomy,” said Albert de Troije, EMEA area program manager for Cook’s embolization devices. “You can shape the tip by hand to create curves that complement specific anatomy. It doesn’t require heat or steam. Cook has the only device on the market like this because of the proprietary braid that runs the length of the microcatheter.”

By using what is at hand, adapting existing tools to new uses, and conceiving of entirely new solutions, innovative Cook product-development staff and brilliant physicians and technicians have collaborated to develop, evaluate, and perfect interventional devices for over 50 years.

By using what is at hand, adapting existing tools to new uses, and conceiving of entirely new solutions, innovative Cook product-development staff and brilliant physicians and technicians have collaborated to develop, evaluate, and perfect interventional devices for over 50 years. Both the Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING) and the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS) are often used during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. The sets’ components are used to access the liver using a transjugular approach and then create a pathway through the liver to connect the portal and hepatic systems, laying the groundwork for the placement of a stent.* Similarly, the Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS) uses a transjugular approach to take a biopsy of the liver.

Both the Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING) and the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS) are often used during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. The sets’ components are used to access the liver using a transjugular approach and then create a pathway through the liver to connect the portal and hepatic systems, laying the groundwork for the placement of a stent.* Similarly, the Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS) uses a transjugular approach to take a biopsy of the liver.

We sat down with Dr. David Beckett, an interventional radiologist at The Whiteley Clinic in London, England, to talk about pelvic congestion syndrome. Dr. Beckett explained the reasons why this painful disease is underdiagnosed and the importance of collaboration among physicians and device companies to get these patients back to living.

We sat down with Dr. David Beckett, an interventional radiologist at The Whiteley Clinic in London, England, to talk about pelvic congestion syndrome. Dr. Beckett explained the reasons why this painful disease is underdiagnosed and the importance of collaboration among physicians and device companies to get these patients back to living.