It started as a “dark art”

Lead management is important now more than ever given the growing number of devices implanted in an aging population. Lead extraction hasn’t always been at the forefront of many physicians’ skillset.

But when pacemakers were a new technology, the medical field had no standard tools or techniques for the procedure then. One pioneer in the field says removing a bad lead back then was “a dark art.”

Pacemakers were a huge step forward in caring for heart patients with abnormal heart rhythms. What no one really thought of at first was what would happen if the pacemaker or the leads attached to the heart needed to be removed or replaced.

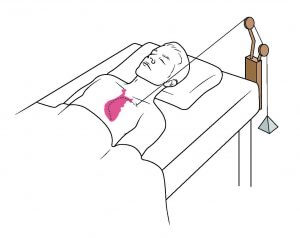

At the time, there was no standard procedure, no tools, no training available to help physicians remove leads. Physicians did the best they could. Some used direct traction—tying sutures to leads or simply pulling on the lead with their hands. Others used a weighted pulley system to gradually apply traction. Yet others approached extractions with open surgery.

Some frustrated physicians became inventors

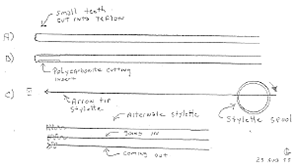

Physicians are problem solvers at heart. Those physicians who were working with pacemakers began to see the need for removing leads, and saw the risks to the patient associated with the methods being used. Several physicians began to innovate and identified the first challenges that needed to be overcome in the procedure: Stability, binding scar tissue, and fragile materials. Some of the efforts to improve lead management include:

- Jorgen Meibom of Denmark began working on a locking stylet that locks at the tip of the lead.

- Charles Byrd of the United States was working on telescoping plastic and stainless steel dilators to separate binding scar tissue from the cardiac lead and to detach the lead from the endocardium.

- The product and engineering team from Cook Medical in the United States was working on a locking stylet and sheaths also, based on the needs they saw watching pacemaker procedures.

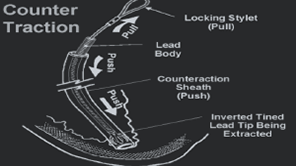

The locking stylet and the concept of countertraction became the core principals behind lead extraction tools.

This image visually explaining counter traction was used in a training PowerPoint developed by Cook Medical.

Iteration and education was a group effort: Collaborating with the core four

A team of product managers and engineers from Cook Medical began collaborating with a core group of physicians on product development: Dr. Charles Love, Dr. Charles Byrd, Dr. Bruce Wilkoff, and Dr. Ray Schaerf. This group had the same goals of creating a safe and effective lead extraction procedure. It was a matter of overcoming technology.

Educating colleagues

This same group began working on training other physicians and raising awareness about managing the risks of lead extraction.

The Heart Rhythm Society (then called NASPE) convened a policy conference in 1997 to formalize standards, training, equipment and staffing recommendations, and indications and contraindications of lead extractions. The guidance document was originally published in April 2000. An updated version was published in 2017.

Sharing lessons

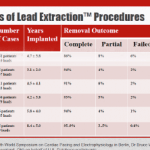

In 1989, Med Institute (the research arm of Cook Medical) began the Lead Extraction Registry to capture procedural data from 400 facilities. Data was collected for more than a decade and then shared to enhance the understanding and practice of lead extraction. This registry was the first study dedicated to lead extraction. It sparked countless other large registries and many physician-written articles continuing to the present day.

We’re never finished improving

Product innovation is always in motion. There is never a point in medical device development or procedure development where you are finished. There is always a way to make the product or procedure better. Additionally, in the case of lead extraction, the technology for pacemakers and leads is always advancing, so lead extraction technology and techniques must keep up. Each new lead creates a new challenge for extraction. From those first, simple products—a locking stylet and a telescoping sheath—the tools for lead extraction have evolved but have not strayed far from those basic principles.

Improved materials, added flexibility, increased strength, more ergonomic features, one-size-fits-all designs—these small changes can add up to big improvements over time.